The university was founded in 1848, when Wisconsin became a state. The campus, which began as a 50-acre site on Bascom Hill, has expanded to cover nearly 950 acres.

Dominating the summit of Bascom Hill and commanding a clear view of the capitol is the Beaux-Arts classical Bascom Hall (500 Lincoln Drive), the campus’s most familiar landmark. It was designed by William Tinsley of Indianapolis and built in 1857–1859 by James Livesay of Madison, but it assumed its present appearance through alterations made from 1895 to 1926. In one unplanned modification, a fire destroyed the rooftop dome. That left the grand Ionic portico as the building’s focal point. The second-story entrance is flanked by sidelights and crowned by a fanlight in the Palladian style. The eighty-five-foot Carillon Tower, located across Observatory Drive, ranks second as a campus landmark. It was designed by Arthur Peabody, who was by then the state architect, and built in 1935. Fifty-six bells peal from the belfry’s double-arched openings.

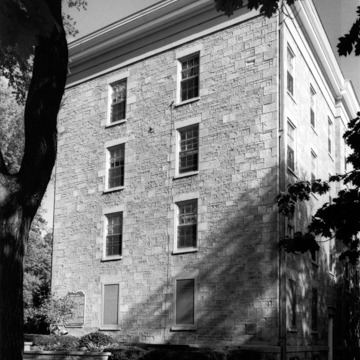

North Hall (1050 Bascom Mall), constructed in 1851, was the campus’s first building. John Rague of Milwaukee created a simple classical composition with pedimented entrances, an unadorned entablature, and plain lintels above the windows. The walls are textured with smooth and rough sandstone blocks and beaded mortar joints. North Hall originally housed lecture rooms, a chapel, laboratories, a library, and dormitory rooms for male students. Naturalist John Muir was a student-resident here from 1861 to 1863. Opposite is North Hall’s twin, the former Agriculture Hall, now called South Hall (1855; 1055 Bascom Mall). Here, the famous Babcock test was developed to determine the fat content of milk.

The Mining Engineering and Metallurgy Lab (1887; 975 Observatory Drive), designed by Henry Koch, is now known as Radio Hall, because from 1935 to 1972 it housed the studios of WHA, one of the nation’s oldest radio stations. The Romanesque Revival building has wide-arched openings and multipaned windows. The murals in the lobby were painted under the auspices of the National Youth Administration (NYA), a New Deal agency that provided work for needy youth and college students during the Great Depression. Next to it is another of Koch’s Romanesque Revival designs, the massive, red brick Science Hall (1887), with rectangular tower-like pavilions, round-arched windows, a broad entrance arch, a rock-faced stone foundation, ornamental brickwork, and glazed terra-cotta trim. Koch’s design called for load-bearing walls, but during construction Allan D. Conover, then a professor of civil engineering, revised the plans to make Science Hall only the second building in the nation (and the oldest surviving one) built with a steel skeleton.

Opposite Science Hall at the base of the hill, Assembly Hall and Library Building (1879; 925 Bascom Mall), now called Music Hall, with its four-stage clock tower and spire, looks more like a church. Local architect David Jones created this High Victorian Gothic gem using alternating blocks of Madison sandstone and Lake Superior brownstone to outline the lancet and ogee arches.

Arthur Peabody likely designed the initial University Club (803 State Street). Gabled parapets, bay windows with stone surrounds, and an arched entrance porch typify Collegiate Gothic, which was popular for academic buildings in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The style often included humorous gargoyle heads such as those on the entry porch caricaturing various university departments and colleges. Built in 1908 and enlarged in 1912 and 1924 according to designs by Law, Law and Potter, the building is home to one of the nation’s oldest faculty clubs. The limestone Wisconsin Historical Society Building (816 State) was built in two stages between 1900 and 1914 (1969 rear addition). Ferry and Clas’s symmetrical composition captures the essence of Beaux-Arts classicism, with a rusticated stone foundation, balustraded roof deck, different window treatments at each floor, and cartouches, leaf-shaped keystones, and console brackets carved as lions’ heads. The interior is a veritable encyclopedia of classical moldings and ornament, including lobby floor mosaics that depict the colophons of Renaissance and colonial-era publishers. The grandest interior space is the three-story Reading Room, with soaring Ionic colonnades, a balcony, and a coffered, stained glass ceiling, restored in 2010. The building originally housed the library. In 1953 the library moved into the sleek, gray stone Memorial Library across Library Mall. Designed by state architect Roger Kirchhoff, the building’s unadorned classicism echoes the rhythms of its older, Beaux-Arts counterpart. Both buildings have a symmetrical four-story facade with a one-story entrance portico flanked by slightly projecting pavilions, with slit-like windows.

Students, faculty, and alumni raised money to erect the rambling Memorial Union (1928; 800 Langdon Street), which overlooks Lake Mendota and is dedicated to the university’s men and women who served in the nation’s wars. Arthur Peabody considered this his greatest work. The Renaissance Revival showpiece has a grand staircase that leads to an arcaded gallery surmounted by a balustraded terrace. The Moderne theater addition to the west dates from 1938. Inside the Union is the much-loved Rathskeller and Stiftskeller, a dining room and cave-like beer hall painted by German immigrant Eugene Hausler with German-style murals and German-language riddles and songs.

Next to the Union is the University Armory and Gymnasium (716 Langdon) known as the Old Red Gym. The building hosted the 1904 state Republican Party convention, which catapulted Robert M. La Follette onto the national political scene and also gave birth to comprehensive direct primaries, a Progressive Era political reform that was subsequently adopted in many other states. The Armory was completed in 1894 and rehabilitated in 1998. It is one of only two remaining buildings on campus designed by the regional firm of Conover and Porter. The fortress-like Romanesque Revival building with crenellated parapets and corner turrets follows a design that was popular for armories after labor disturbances rocked the nation in the late 1880s. In 1970 antiwar protesters firebombed the Armory, heavily damaging the first floor.