You are here

West Virginia Independence Hall (U.S. Customhouse, Post Office, and Courtroom)

From 1852 to 1862, Ammi B. Young held the position of Supervising Architect of the U.S. Treasury Department, the agency responsible for the design and construction of federal buildings. He often employed the Italian Renaissance Revival style, which he called “Italian with Greek details,” in his work. Young's Wheeling building, though an excellent example of the type, was virtually identical to the Cleveland Customhouse and differed little from buildings that he designed for Georgetown (Washington), D.C.; Portsmouth, New Hampshire; and Bath, Maine, among others.

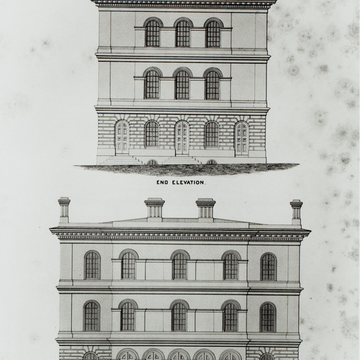

The three-story building is faced with locally quarried sandstone, rusticated on the ground story but finished with smooth, coursed ashlar blocks above. Encircling belt courses firmly delineate second- and third-floor levels, and a full, finely detailed cornice caps the ensemble. The three central bays of the five-bay Market Street facade project slightly to form an entrance pavilion.

Although the exterior walls are load bearing, the interior frame has locally manufactured cast iron columns and stairways and wrought iron beams and girders. Door and window frames are also of iron. The extensive and early use of iron ensured that the building was as fireproof as it could possibly be.

Independence Hall is notable not only for its architectural merit; it is one of West Virginia's most historic structures. With the full consent of Wheeling's postmaster and collector of customs, it housed the most important session of the Second Wheeling Convention, a meeting that was instrumental in creating the new state of West Virginia. In June 1861, the convention assembled in the third-floor courtroom. Here it adopted “A Declaration of the People of Virginia,” which declared the secessionist government in Richmond illegal and established the Restored Government of Virginia. After the convention adjourned, legislative sessions were held in the same space, while newly elected Governor Francis H. Pierpont occupied a second-floor office. The Wheeling Daily Intelligencer, a major proponent of the new-state movement, declared the then-new building “a good deal finer than the one tenanted by the traitors at Richmond,” referring to Thomas Jefferson's Virginia State Capitol. From November 1861 to February 1862, delegates to the Constitutional Convention met in the building, arguing questions of debt and slavery and selecting a name for the new state. When West Virginia became the thirty-fifth state on June 20, 1863, the legislature moved to nearby Linsly Institute ( WH5), and in 1864 the executive branch followed. West Virginia's Independence Hall then reverted to its original uses.

Soon after, the first in a long series of remodelings began. Because of design problems, exacerbated by Wheeling's coal-laden atmosphere, the low-pitched iron roof had rusted. In

When a new federal building ( WH17) was constructed early in the twentieth century, Young's building was sold to private interests and enlarged from designs by Frederic F. Faris to become an office building. Faris replaced the “wart” with a two-bay addition that extended the building to the 16th Street sidewalk. Still later, a fourth story was added, and a shallow Ionic portico was attached to the Market Street facade.

In 1964 the state purchased the property and leased it to the West Virginia Independence Hall Foundation, a group of Wheeling citizens formed to oversee a restoration that would return the building to its Civil War–era appearance. Under the auspices of the National Trust for Historic Preservation, Tony P. Wrenn prepared a master plan, and a painstaking restoration was begun in 1969–1970 under the direction of Wheeling architect Tracy R. Stephens. In 1980 the foundation, having accomplished its mission, returned Independence Hall to the state, which now operates it as a museum and regional office for its Division of Culture and History. In 1985 Stephens received an award from the West Virginia chapter of the American Institute of Architects for his work. In 1986 Paul D. Marshall and Associates prepared a historic structures report. The U.S. Secretary of the Interior declared the building a National Historic Landmark in 1988, a fitting testimonial to West Virginia's birthplace.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.