The University of Wyoming (UW), the state’s only four year institution of higher education, is significant for its role in the development of Wyoming's human resources, industries, and institutions from territorial days to the present. As a land grant college, the school has traditionally provided residents of Wyoming with a broad education in the arts and sciences, while contributing to the intellectual, cultural, and economic development of the state. In addition to its important role in the history of the state, the UW campus is probably Wyoming’s best example of a designed landscape, and it contains distinctive buildings from all eras of the state’s history, most of them designed by prominent Wyoming architects and reflecting national trends in collegiate architecture.

Today, the campus occupies the equivalent of about 200 city blocks (785 acres) on what was originally the eastern edge of Laramie (the city has since expanded several miles to the east of campus). The original campus, or West Campus, was developed from 1886 until World War II, with building replacement and infill continuing to the present. The East Campus, east of Fifteenth Street, was developed starting in the 1930s with a fraternity row, and the campus continues to spread east and north today. Several homes in the surrounding University Neighborhood (now a National Register Historic District) have been purchased by the University and added to the campus.

The University of Wyoming was founded in 1886, when Wyoming was still a territory, on 10 acres of land donated by the city and an additional 10 acres purchased from the Union Pacific Railroad. Situated on a rise east of downtown, the campus grew up around what was originally called University Hall, now known as “Old Main” (1886). This Romanesque Revival building functioned as classroom, administration office, library, and cafeteria, and early photos show it standing alone, on a treeless plain with no other buildings in sight. By the early 1890s, grading was initiated, grass was planted, and a flagstone walk was installed connecting Old Main with Ninth Street to the west. An ambitious tree-planting campaign was initiated in 1892. Landscaping was a continuous process, and gradually improved the appearance of the campus. Around 1905, a diagonal stone walkway was installed connecting the southwestern corner of the campus to Old Main. A 1918 catalogue noted that, “with the extension of the system of walks and drives, the grounds are taking on the aspect of the traditional college campus.”

The early growth of the university was somewhat haphazard, with land and buildings added as they were needed and when funding was available. A “Hall of Science” was built to the north of Old Main in 1902, followed by Merica Hall, a women’s dormitory in 1907 and then Agricultural Hall (later Biochemistry, 1914) and a second dormitory (Hoyt Hall, 1916/1921). In all, 7 new buildings (of which 4 remain) were added between 1902 and World War I. Old Main and the two dormitories bounded an open, park-like space that remains today because the state legislature declared it a state park in the 1950s to prevent it from being developed.

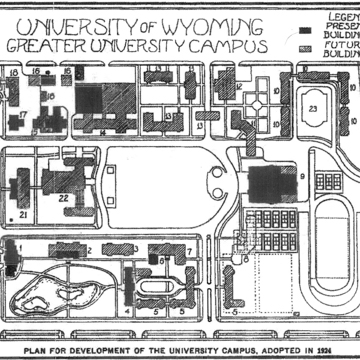

A growing number of students, especially after World War I, led to a campus expansion to include more housing, a new library, an engineering building, and a gymnasium. Fortunately for the university, oil was discovered on university-owned land in 1916, and within five years the state legislature appropriated funds from oil royalties to support the building campaign. UW President Arthur Crane championed the idea of a campus plan to avoid “piece-meal and haphazard” construction. The university hired architect Wilbur Hitchcock, a member of its own faculty, and the Denver-based landscape architecture firm of McCrary, Culley and Carhart to develop plans for a “Greater University.” The 25-year campus master plan the design team developed in 1922–1924 reoriented the campus around a central open space surrounded by a quadrangle of buildings northeast of Old Main. The space, which came to be known as Prexy’s Pasture (1928), functioned as a commons for students to gather, socialize, and exchange ideas. In addition to laying out walkways, roads, building sites, landscaping, and utilities, the plan conceived a standardized architectural image, through the use of design guidelines developed by Hitchcock with the assistance of New York architect Raymond Hood.

Although the actual design guideline documents have been lost, based on contemporary accounts and on a study of the buildings produced while they were in effect, it is clear that Hitchcock and Hood attempted to ensure compatibility while giving individual buildings distinctive identities. On the West Campus the guidelines were followed throughout the 1960s; here, the buildings are constructed of native buff-colored sandstone from the university's quarry, giving them continuity in color and texture. With the exception of the first university library (now Aven Nelson Hall), the pre-1955 buildings all have a vertical emphasis, with piers and receding vertical masses or stepped-back masonry forms reflecting the terrain of the nearby Snowy Range. Later buildings reflect the post-war influence of International Style modernism. Building styles range from Beaux-Arts (Half-Acre Gymnasium, 1923) to Collegiate Gothic (McWhinnie Hall, 1928; Agricultural Hall, 1949) to Art Deco (Engineering Hall, 1927) to Depression Moderne (Arts and Sciences, 1936; Wyoming Union, 1938) and International Style (Education Building, 1950; Coe Library, 1958).

In 1931, UW commissioned Denver landscape architect S.R. DeBoer to study the existing campus plan and make recommendations for improvement and expansion. In addition to general recommendations for the west campus, DeBoer developed a plan for extending the campus east, across Fifteenth Street, with a Fraternity Park—something that had been envisioned by Hitchcock before his untimely death in 1930. DeBoer also recommended that campus buildings be grouped according to four major uses: education (library, classroom, and laboratory buildings), recreation (gymnasium, stadium, athletic fields), residential (dormitories, fraternity and sorority houses) and administrative (offices for President, Deans, Registrar, etc.). Although nothing could be done about existing buildings, post-1931 construction generally followed DeBoer's principles for siting campus facilities.

Like most campuses nationwide, UW experienced a surge in enrollment after World War II, expanding its facilities as needed. Several buildings were added to the West Campus during this period and others were remodeled or expanded, but the real growth took place to the east. Brutalist “high-rise” dormitories—White, Downey, McIntyre, and Orr Halls—were built in 1965–1967 along Grand Avenue, while fraternity and sorority houses were arranged on either side of a grassy open space as designed by DeBoer. Athletic facilities were pushed further east, with a new stadium, field house, gymnasium, and arena. UW continues to expand in this direction.

The new buildings added to the Laramie campus in the post-war period reflect a growing divergence from the architectural design tradition established by architects Wilbur Hitchcock and Raymond Hood in the mid-1920s. While some are significant expressions of mid-century modernism, such as the Classroom Building (1968) and the Crane-Hill dormitory/cafeteria complex (1962), others are more utilitarian with aesthetics subordinate to function, as in the massive additions to Engineering Hall and Coe Library. The 1993 American Heritage Center/Centennial Complex and the 2012 Visual Arts Facility are exceptions. In 2015 the campus underwent a review of its architectural and historic preservation policies, creating design guidelines to bring future construction more in line with early-twentieth-century aesthetics.

References

Marmor, Jason D., “University of Wyoming Campus, Laramie, Albany County, Wyoming: Written Historical Data,” HABS No. WY-116. Denver, CO: Historic American Buildings Survey, National Park Service, Dept. of the Interior, 1994.