The queen of Phoenix resorts, the Arizona Biltmore, opened in February 1929, only eight months before the stock market crash triggered the Great Depression. As the centerpiece of an upscale housing development, the hotel fostered suburban growth in central northeast Phoenix while solidifying central Arizona’s status as a seasonal resort destination with a thriving leisure industry. Exhibiting a signature Wrightian style, the Arizona Biltmore is a product of Wright’s one-time draftsman, Albert Chase McArthur.

Charles and Warren McArthur, sons of early Wright client Warren McArthur Sr., relocated from Chicago to Phoenix soon after Arizona statehood and became distributors for Dodge motorcars. By the 1920s, they were among Phoenix’s leading entrepreneurs and envisioned the development of a luxury resort in the desert that would attract affluent winter visitors to the city from the Midwest and elsewhere. In 1927, their efforts to finance the project were realized when they reached an agreement with Bowman Biltmore Hotels and other investors to build a winter resort on a property eight miles northeast of Phoenix. The development, occupying 600 acres of land at the foothills of Piestewa Peak, was to consist of a hotel and golf course on 200 acres of citrus orchard land with the additional 400 acres subdivided for residences.

The McArthur brothers recruited their older sibling Albert, an architect educated at the Armour Institute of Technology (later IIT) and Harvard, to design the hotel. Albert McArthur had worked for Frank Lloyd Wright and was interested in using Wright’s “textile” concrete block system at the Biltmore. Believing Wright had patented the system, McArthur offered to lease it from Wright and asked him to serve as his design consultant and oversee the installation of the block system. Almost 60 and threatened by financial and marital difficulties, Wright wired his acceptance immediately, arriving by train within days. McArthur subsequently learned that Wright did not own a patent for the block. Wright, meanwhile, was alienating McArthur’s associates, and, after only four months at the Biltmore site, the younger architect was forced to ask his mentor to leave.

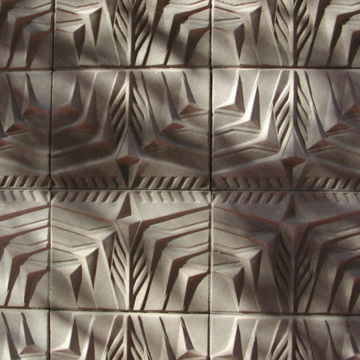

Built between 1928 and 1929, the irregularly massed hotel is composed entirely of “Biltmore Blocks,” or sculpted, precast concrete blocks formed on-site using desert sand. The 34 distinctive, geometric patterns of the blocks were inspired by the crisscrossed pattern of the trimmed trunks of palm trees and were designed by the Austrian-born photographer and sculptor Emry Kopta, who was known for his work among the Hopi Indians. Wright’s wife, Olgivanna, called the patterns “abstracts inspired by cacti,” while Warren McArthur III, Albert’s nephew, claims they represented Albert’s theories on light frequencies and musical tones. In any case, the use of desert botanical motifs suggests that McArthur shared Wright’s belief that buildings should harmonize with the forms and patterns of their surroundings.

Arriving guests entered the main building via a 200-foot-long lobby, its high ceilings glittering with gold leaf. In the adjoining Aztec Room, a maze of copper-filigreed beams supported an elegantly domed ceiling, also covered in gold leaf. Other ancillary spaces included a sunroom, secluded alcoves, gift shops, and a stockbroker’s office. With its bookcase that converted into a liquor cabinet, the men’s smoking room (later called “The Mystery Room”) was popular during Prohibition. The hotel’s 243 original guest rooms were located in the main building and 15 cottages arrayed on the grounds.

After the financial collapse of October 1929 bankrupted the McArthurs, chewing-gum magnate William Wrigley Jr., one of the Biltmore’s initial investors, assumed ownership. At first, Wrigley opened the hotel only to high-society members of his acquaintance. In 1931, he constructed his own 18,000-square-foot residence, La Colina Solana (popularly known as “The Wrigley Mansion”), on a five-acre hilltop site overlooking the Biltmore and subsequently opened the hotel to a broader spectrum of guests. That same year, Wrigley hired local architect and builder Robert T. Evans to add the resort’s first swimming pool. The Catalina Pool is distinguished by bright yellow and deep blue tiles from Wrigley’s Catalina Clay Products (also known as Catalina Island Pottery for its California location). Evans also designed and built a bath house and 20 cabanas. During the same period, the golf course was completed and construction began on houses in the adjacent Biltmore Estates. Wrigley’s son Philip assumed control of the Biltmore after his father’s death in 1932. Under the Wrigley family’s management, the hotel gained fame nationally as a luxury resort where the rich and famous could enjoy a weekend getaway or an entire season, privacy assured.

In May 1973, the Biltmore was sold to Talley Industries. Two weeks later, while the hotel was closed for remodeling, a welder’s torch sparked a fire that destroyed the fourth floor and significantly damaged those below. Losses totaled $2.5 million—equal to the hotel’s original construction costs. Talley retained Taliesin Associated Architects, Wright’s successor firm, to oversee reconstruction. Taliesin Architects specified a bold geometric decor of yellow, mint green, orange, and blue, while gold leaf was reapplied to the ceilings. Concrete blocks were cast on-site, replacing those damaged by the fire. A graphic design created by Wright and entitled “Saguaro Forms and Cactus Flowers” was rendered in glass and became the focal point of the new entry area. Taliesin Architects also oversaw additions to the historic core that were indistinguishable from the original buildings, due to their extensive use of Biltmore Blocks. The first major expansion was the Paradise Wing (1975), which holds 89 guest rooms. This was followed by the construction of the 120-room Valley Wing (1979), a 39,000-square-foot conference center (1979), and the 109-room Terrace Court (1982). In recent years, though the hotel has changed hands several times, further expansions and renovations have largely preserved and enhanced its Wrightian character. Today, the Biltmore contains 740 rooms and is one of the state’s largest hotel and event venues.

Though controversy over the identity of the original architect has long plagued the Biltmore, the architect of record is McArthur, although he had never designed a building of this scale prior to this commission, nor did he ever equal the achievement afterward. While still on the job site, Wright was already rumored to be the hotel’s designer. Wright, at McArthur’s request, wrote a letter in 1930 stating, “Albert McArthur is the architect of that building—all attempts to take the credit for that performance from him are gratuitous and beside the mark. But for him Phoenix would have had nothing like the Biltmore, and it is my hope that he may be enabled to give Phoenix many more beautiful buildings as I believe him entirely capable of doing so.” Some years later, however, Wright wrote McArthur’s widow, saying, “I have always given Albert’s name as architect…and always will. But I know better and so should you.” Although Olgivanna Wright felt her husband had done most of the design for the Biltmore, Warren McArthur III, Albert’s nephew, has emphatically stated in print that Wright made little contribution. After extensive study of Albert Chase McArthur’s letters, papers, and drawings relating to the Biltmore, architectural historian Bernard M. Boyle, concluded that Wright’s influence was only secondary, and likely came from the years McArthur worked for him. Through it all, the Arizona Biltmore has maintained its status as one of America’s great resorts in addition to its role as a catalyst for the development (and redevelopment) of Phoenix northeast of the original townsite.

References

Elmore, James W., FAIA, ed. A Guide to the Architecture of Metro Phoenix. Phoenix: Central Arizona Chapter American Institute of Architects, 1983.

Legler, Dixie, and Scot Zimmerman. Frank Lloyd Wright: The Western Work. San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 1999.

Miles, Candice St. Jacques. Arizona Biltmore: Jewel of the Desert. Phoenix: Arizona Biltmore, 1985.

Nilsen, Richard. “The Arizona Biltmore and the influence of Frank Lloyd Wright.” The Arizona Republic, July 19, 2011.

Patterson, Ann, and Mark Vinson. Landmark Buildings: Arizona’s Architectural Heritage. Phoenix: Arizona Highways, 2004.

Whiffen, Marcus, and Carla Breeze. Pueblo Deco: The Art Deco Architecture of the Southwest. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1984.