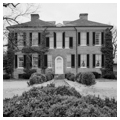

Among Maryland’s most distinctive domestic building forms is the five-part Palladian house, consisting of a central block flanked by hyphens and terminating wings. It first appeared in Maryland in and around Annapolis in the 1760s, embraced by the city’s wealthier classes. It spread throughout the Chesapeake region, serving in rural areas as the centerpiece of a plantation or along the urban fringes as a country retreat or gentleman’s farm. The five-part design was based on the work of sixteenth-century Italian Renaissance architect Andrea Palladio, who took his inspiration from classical antiquity, predominately the use of the classical orders and the emphasis on symmetry and proportion.

Palladio outlined his revival of classical design in The Four Books of Architecture in 1571. First published in Britain in 1715–1720, his design concepts were enthusiastically adopted by British architects, launching the Anglo-Palladian movement and Georgian mode of architecture. Gaining popularity, these designs were translated into pattern books and builder’s guides. By the mid-eighteenth century, Palladian-influenced design had reached the American colonies through both pattern books and immigrant architects and artisans.

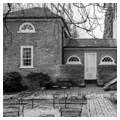

The Maryland prototype corresponds with Palladio’s country villa, which incorporated low-flanking arcades connecting to wings designated for agricultural use. These hyphenated wings became an integral part of the houses designed by Palladio’s eighteenth-century colonial enthusiasts, best embodied by the Hammond-Harwood House. The form appeared most frequently in the southern colonies where it was easily adapted to the regional tradition of building separate dependencies; the wings served to isolate heat generated by functions such as food preparation. One wing of Maryland’s five-part house was thus dedicated to kitchen and service areas, while the other was used for more secluded business or family functions. Likewise, the characteristic Palladian temple-front portico, often more simply translated as a pedimented central pavilion, was an exterior articulation of the interior Georgian center-passage as at His Lordship’s Kindness.

So popular was the five-part plan by the latter part of the eighteenth century that many earlier Georgian houses were expanded to encompass the characteristic hyphenated wings such as Tulip Hill and Montpelier. The form persisted into the early nineteenth century, embracing Adamesque or Federal period motifs as seen in Homewood and Riversdale. While the plan fell out of favor by the second quarter of the nineteenth century, it reappeared in such Colonial Revival residences of the early twentieth century as exemplified by the Newton White House.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.