You are here

Mesa Arizona Temple

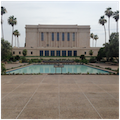

Since the time of its dedication in 1927, the Mesa Arizona Temple has been the heart of religious service for members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS) within the local community and throughout the Southwest. Indeed, from the late 1870s through the 1950s, most Mesa citizens were members of the Mormon Church. Even as Mesa’s demographic profile changed dramatically with the exponential growth of metropolitan Phoenix in the decades after World War II, the Mesa Arizona Temple remained a regional center of faith, and a city landmark.

The Mesa Arizona Temple is located on the eastern fringe of the mile-square Mesa City townsite of 1883, with the temple grounds and the city’s Pioneer Park mirroring one another across Main Street. In selecting this Main Street site for the Temple in 1920, LDS church leaders were strategic, and even prescient: already an important regional road, Main Street would soon become part of the transcontinental U.S. Highway 80. Mesa itself was an ideal location for the Temple, being central to other Mormon settlements in Arizona, and those in Southern California and Mexico. The Temple became a major attraction for tourists from inside and outside the Mormon Church.

The first LDS temple built in Arizona (and among the first three LDS temples built outside of Utah), the Mesa Arizona Temple took more than four years to complete, from groundbreaking on April 25, 1923 to dedication on October 23, 1927. Before its construction, Arizona Mormons performed temple ordinances (ceremonies) in the Temple in St. George, Utah. Because so many bridal parties traveled the wagon road between St. George and Arizona, the worn path became known as the Honeymoon Trail.

Church leaders set the lofty goal of perfection for the design, materials, and workmanship of the new edifice and at the time of its completion, the Mesa Arizona Temple was the most expensive building ever constructed in the state; at $800,000, it cost several times more than the Arizona Capitol. Notable for having no traditional spire, it was obviously influenced by the architectural vocabulary and compositional symmetry of Beaux-Arts classicism. The flat-roofed Mesa Arizona Temple also possess a remarkable similarity to the massing and form of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Barnsdall Hollyhock House in Los Angeles (1921). The simplified, classically derived facades of this Temple also presages and parallels the stripped classicism and federal Moderne style of the late 1920s and 1930s, exemplified in Paul Cret’s Folger Shakespeare Library and the 1937 Federal Reserve Building [DC-01-FB08], both in Washington, D.C.

The grounds of the Mesa Arizona Temple are laid out in a formal geometric pattern that anchors the main religious building to the earth and lifts it to the sky as a symbolic axis mundi. As in ancient temples, imperial palaces, and numerous examples of geomancy in design (like the Forbidden City in Beijing), the Mesa Arizona Temple and grounds are oriented to the cardinal directions.

To provide unobstructed primary views of the Temple, the placement and selection of trees was well considered. For the most part, the twenty-acre property is an open, irrigated lawn with thematic gardens, flower beds, terraces, and reflecting pools around the Temple. The plant materials are both native and exotic. The selection of trees and shrubs from five continents is meant to be interpreted as an embrace of the people from all over the world. Desert plants and cacti represent the Native Americans and Mexicans so important in the growth of the LDS Church during the mid-twentieth century.

The landscape design works at all scales—for solitary contemplation and for celebrations by thousands. In recent decades, a detached visitor center and terrace with reflecting pool were constructed north of the Temple. Their careful placement and scale enhance the presence and importance of the larger Temple by providing a vantage point and procession way. And despite their intrusion, the grounds remain one of Arizona’s few surviving early-twentieth-century landscape designs.

The design of the Temple is graceful in form, restrained in ornamentation, and harmonious in proportion. In both plan and elevation, the building maintains quiet, firm, and dignified simplicity. Ornamentation is used sparingly, perhaps reflecting the Mormon pioneers’ “waste nothing” ethos. The tripartite division of the two-story facades takes advantage of an underlying playful pattern of the “divine proportion” to create simultaneous perceptions of repose and motion.

The Mesa Arizona Temple conveys a character of permanence, strength, and sanctity through its low, box-like shape standing firmly upon the center of a broad, one-story platform. This first-floor base was extended to the south in 1975 to add more support facilities for increased visitation and religious uses. The 17,000-square-foot expansion, designed by LDS church architect Emil Fetzer, brought the total area of the Temple to 113,916 square feet. The axially symmetrical, two-story Temple is 128 feet wide by 184 feet long and 55 feet high, with exterior walls nearly four feet thick. An expansive terrace, four feet above street level, surrounds the Temple platform. A monumental, white Vermont granite staircase rises from street level to the terrace and up to the main entrance doors on the west.

The building appears as a typical Classical Revival composition, even if it lacks the expected details and features of the classical orders. The paired columns and piers are squared not rounded. The column capitals have a single row of elongated, stylized acanthus leaves rather than the overlapping design of the Corinthian order. The cornices are shallower than in classical examples. The corner friezes are decorated with bas-relief sculptures of the gathering of Latter-day “Israelites” from around the world to their promised land in America. The frieze motif was designed by A.B. Wright and sculpted by Torlief S. Knaphus. Both men were well-known for their artistic contributions to LDS temples and churches. The outside walls are veneered with a glazed, cream-colored “pulsichrome” terra-cotta tile from the Gladding-McBean Company of California. Each glistening tile was marked at the fabrication plant to guide its exact placement on the facade and to assure its perfect fit into the bonding pattern.

The reinforced concrete foundation walls vary between ten and twelve feet thick. The structural framework of the Temple is a system of reinforced concrete columns and beams. Concrete floor and roof decks cast on steel forms span between the beams. More than a million clay bricks fill the thick exterior walls within the concrete framework and between the outer and inner finished wall surfaces.

The Temple is used for special religious services and ceremonies rather than for regular congregational worship. The 193 rooms of the Temple serve functions of preparation, instruction, ceremony, and support. Only church members in good standing may enter the Temple beyond the entrance foyer. The Temple’s floor plan and spaces symbolize mankind’s upward progression in returning to the presence of the Heavenly Father. Murals painted on canvas cover the walls of the central hall and tell the story of LDS founder Joseph Smith and depict scenes of the Mormon experience. The interior volume centers on the black marble grand staircase that patrons see as they enter the Temple. Church members ascend the staircase after they have changed into white temple clothing, received instruction, and completed an endowment session. They proceed up the staircase and into the Celestial Room, symbolizing the achievement of exaltation. An expansive skylight, executed in a spiderweb design of pale-tinted glass, illuminates the grand staircase, creating the other-worldly atmosphere of the great central hall. The main rooms in the upper stories are used for religious lectures and the performance of religious ordinances. These large rooms are adorned with instructive and inspirational murals appropriate to the theme and purpose of the room—Creation Room, Garden Room, Lone and Dreary Room, Terrestrial Room, and Celestial Room.

In the first-floor baptistery, twelve full-scale sculpted oxen shoulder the twelve-foot-diameter by four-foot-deep baptismal font. This important ceremonial feature was modeled after the oxen-supported purification basin in Herod’s Second Temple in Jerusalem, symbolizing the twelve tribes of Israel. The oxen are also emblematic of the beasts of burden that hauled the Mormon pioneers’ wagons across the American plains to build their “City of Zion” on the Great Salt Lake and, thereafter, to establish Mesa, Arizona.

References

Hawkins, Chad S. Temples of the New Millennium. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book Company, 2016.

Hughes, John. Deseret News 2001-2002 Church Almanac. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret News, 2000.

Lundwall, N. B. Temples of the Most High. Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1961.

Mead, Tray C., and Robert C. Price. Mesa – Beneath the Shadows of the Superstitions. Northridge, CA: Windsor Publications, 1988.

Mesa Arizona Temple. “History of Mesa Arizona Temple.” Unpublished manuscript, n.d. Mesa Arizona Temple, Mesa, Arizona.

McIver, Walter A., “Mesa Arizona Temple (of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints),” Maricopa County, Arizona. Draft of a National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form, 2001. Mesa, Arizona.

Plewe, Brandon S. Mapping Mormonism: An Atlas of Latter-day Saint History. Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University, 2014.

Ryden, Don W., “Temple Historic District,” Maricopa County, Mesa, Arizona. National Register of Historic Places Inventory–Nomination Form, 2000. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.