You are here

Edwards Peters House

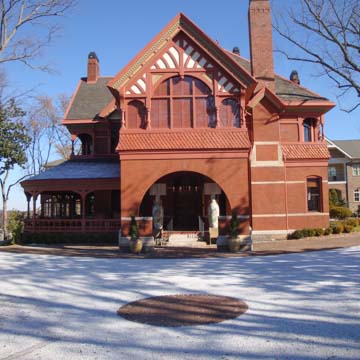

An engineer with the recently chartered Georgia Railroad, Richard Peters first came to Atlanta, then called Marthasville, in 1844. The Georgia Railroad was projected to run between Augusta and Athens, with a branch extended to Madison; Marthasville, originally named Terminus, was the end of the line of the Western and Atlantic Railroad, and Peters saw merit in connecting the railroad towns. Under urging from Peters, Marthasville was renamed Atlanta in 1845 and Peters settled there permanently the following year. Land was cheap in those early years of Atlanta’s history, and Peters began to amass a considerable amount of it, including two land lots totally some 400 acres north of North Avenue in what is now Midtown Atlanta. In 1871, Peters and George W. Adair organized the Atlanta Street Railway Company, the city’s first trolley line, and by 1878 it connected downtown businesses to Ponce de Leon Avenue, extending northward through the entire Peters land to Eighth Street by 1893. It was on a full city block site on Ponce de Leon Avenue that Peters built Ivy Hall in 1883 as a wedding gift for his son, Edward, who would inherit his father’s business enterprises and extensive landholdings after his death in 1889.

The 4,400-square-foot mansion, designed by Gottfried Norrman, was the finest house in the “Peters Park” development, and one of the first in Atlanta to display the ornamental richness of the Queen Anne Style. Other wealthy residents, attracted to the area because of the trolley line, commissioned fine houses from prominent builders of the day, including Norrman, W. T. Downing, and Bruce and Morgan; Peachtree Street and Piedmont Avenue became the most prestigious streets. As the neighborhood density increased, bungalows and simpler middle-class dwellings were built along Myrtle and Argonne streets. Peters’s development, like Inman Park to the east, was a classic streetcar suburb, successful because the trolley (at first horse-drawn and later electrified) provided convenient transportation to work.

While large houses built in Atlanta during the 1880s employed certain features—broad gables, rambling porches, tall chimneys, bay windows, turrets, towers, and rooms of varied configurations—of a new domestic style, few displayed the kind of extensive ornamental enrichments and variety of materials evidenced at Ivy Hall. The new aesthetic was stylistically variegated, a cocktail of ingredients from English Queen Anne, influences from Charles Eastlake’s Hints on Household Taste, and a bit of the American Shingle Style. Ivy Hall was resplendently Queen Anne, manifesting the “art for art’s sake” spirit of the Aesthetic Movement and finding at every turn an opportunity for decorative display. In evidence here were ornate fireplaces, wallpapers, plaster friezes, staircase woodwork, High Victorian chimneypieces, beveled glass, accents of stained glass, Lincrusta Walton, ceramic tile work, and terra-cotta—each an exercise in excessive decorating, varying textures, and unrestrained ornamental display. During a 2009 renovation, craftsmen were careful to preserve, for instance, the rare curly pine paneling in the smoking room, the foliate Lincrusta panels, the dining room fireplace scenes referencing the Philadelphia Fish and Chowder Society founded by the Peters’s ancestor, Judge Richard Peters, and the many other carved, molded, or cast furnishings of the house.

Ivy Hall has experienced several near misses in events that might well have brought about its destruction. In 1917, Atlanta’s great fire swept across the city’s fourth ward toward the Peters property. After some 300 acres had been consumed, firefighters began to dynamite houses between North Avenue and Ponce de Leon Avenue to create a fire break. Ivy Hall, however, was spared and the fire brought under control, although it destroyed nearly 2,000 houses, businesses, and churches, displacing approximately 10,000 people. The mansion remained in the Peters family until 1970, when Edward’s daughter-in-law Lucille died. For a few years, it remained mostly vacant, although it was used briefly as a drug rehabilitation center.

Due to its extensive, full city block property, the house was an attractive target for development and in 1973, with minimal intrusions on original building fabric or ornament, it was repurposed as the Mansion Restaurant. Across the street a similar adaptive reuse had converted Charles H. Hopson’s 1915 Ponce de Leon Methodist Episcopal Church into the Abbey Restaurant, and both landmarks became favorite Atlanta dining spots. In 2000, however, a fire damaged the upper part of Ivy Hall, prompting the restaurant to close. After the fire, a developer sought a demolition permit for the house in order to build multi-family housing, but was denied approval by the Atlanta Urban Design Commission. Although the developer took steps to challenge the ruling, the commission called for preservation groups and the new owners of the property to find a resolution that would preserve the house, even if parts of the property were to be utilized for new multi-family development. The Savannah College of Art and Design (SCAD), who had experience in restoring historic properties for their use in Savannah, acquired the house for the school’s expansion to Atlanta. Following eighteen months of study and research, and a meticulous and award-winning restoration by SCAD and Surber Barber Choate and Hertlein Architects, Ivy Hall was converted into a writing center for the art school. Multi-family housing, known as the Ivy Hall Apartments, was built on the remainder of the city block, to the south and east of the house.

References

Bierig, Aleksandir. “SCAD Comes to the Rescue of Atlanta’s Ivy Hall.” Architectural Record, May 26, 2006.

“Edward C. Peters House.” National Park Service Atlanta: A National Register of Historic Places Itinerary. Accessed July 6, 2016. http://www.nps.gov/.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.