You are here

Glenridge Hall (Demolished)

Glenridge Hall was the most notable Tudor Revival country house in Georgia, and likely in the entire South. It was designed in 1928 by Samuel Inman Cooper for Thomas Glenn, who was president and chairman of Trust Company Bank (now SunTrust Bank) and who had owned the land since before World War I. The dwelling, sited fifteen miles north of downtown Atlanta, was more in the tradition of an English country house than a suburban Atlanta residence.

A winding drive led from a distant entry through a natural wooded landscape to Glenridge Hall, a rambling manor house that first disclosed to the viewer its picturesque forms through gaps in the trees. The drive then opened to a veritable stage set of picturesqueness, a great house whose extended wings reached out and forward to embrace the visitor. Half-timbering mixed with the rich texture of an almost rustic red brick, calls to mind centuries of historic English country houses whose timeless slate roofs, as here, hover over shifting building masses accented by gables and tall chimney stacks. The patina of the Glenridge Hall’s architectural surfaces suggests an expression of ancient lineage and historic roots that was sought after in 1920s America and convincingly evidenced in residential architecture of various eclectic styles, but rarely equal to here. Among the stylistic choices architects of the period offered residential clients was the Tudor, which, perhaps even more than the American Colonial or Classic Revival, suggested home and heritage, two distinctly Southern values of family ancestry whose roots go back to medieval England.

Samual Inman Cooper played the “game” of architecture, as his contemporary Sir Edwin Lutyens often characterized the profession, producing house designs that embodied a fictitious history. This aged character was effectively achieved through building features and design devices that implied that a house embodied a history that reached back generations. At Glenridge, butterfly joints appear to patch floor boards, and repairs are inset haphazardly along joints as though necessitated by splits in the boards from years of wear and tear. Similarly, in windows, fragments of “repair” leading are in evidence that appear to mend window panes that had, in fact, not actually cracked. In other Cooper and Cooper houses, where designers called for whitewashed exterior brick, the architects carefully selected a paint that would immediately weather. Such devices gave the house the impression of age.

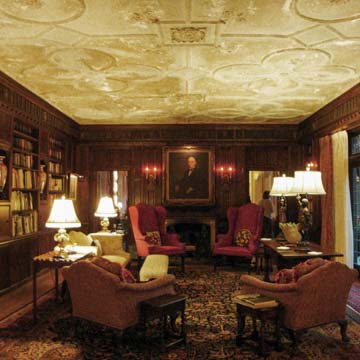

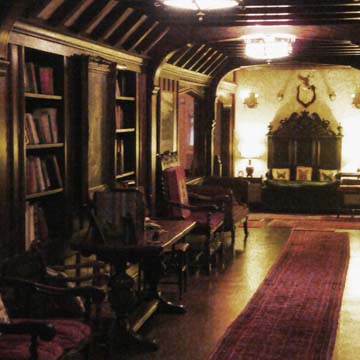

The most striking space within the house was the great hall. Capped by massive wood trusses, this was a vast room overlooked on two sides by open corridors that served as upper balconies or minstrel galleries. The great hall was the heart of the English country house. Along the long garden side of the Glenridge great hall, opposite the entry, was a welcoming inglenook with fireplace, the very personification of English comfort and domesticity in which home and hearth are equated. The ceiling of the library was adorned with stuccowork of quatrefoils and raised geometric patterns, continuing the English references.

Furnishings throughout reinforced the family’s interest in history and the traditional, including a noble carved-oak, four-poster bed. Dark woodwork in furniture, wall panels, trusses, and exposed architectural framing, especially within and around the great hall, brought a masculine character to the public rooms. Elsewhere, however, an almost eighteenth-century Gothick architectural detailing, light and feminine, with delicate groined vaulting and more refined pointed arches, offered balance. An intimate breakfast room was adorned with landscape murals painted by Athos Menaboni, and an Oriental room was enriched with Chinese porcelain, bird and floral panels, and other refined decorative arts, another contrast to the trumpet fanfare of the great hall.

Glenridge Hall did not directly quote specific houses in England, as does, for instance, Stan Hywet in Akron, Ohio, nor is Glenridge an artificial “stockbroker Tudor,” as so many suburban houses surrounding American cities often aspire to be. Nor is Glenridge quaint, as contemporary cottages in the Morningside district of Atlanta might be described. What all these neo-medieval house types share is a picturesque juxtaposition of traditional building forms and materials, an architectonic richness that begins with the premise that a house must be beautiful and that architecture is a work of art. Compared to the formality of Hornbostel’s Callanwolde in Atlanta, Cooper and Cooper’s country Tudor at Glenridge is comfortably informal, homey, and picturesque in the late-eighteenth-century sense of understanding the inmate relationship of architecture and landscape.

The 2015 razing of the great house and redevelopnent of the site is all the more tragic due to the supreme merits of this place with respect to both architecture and the estate’s extensive preserved natural wooded landscape. The lost opportunity to meld Atlanta’s suburban tradition of well-landscaped corporate campus design with the essentials of sustainability in preserved landmark architecture is historically significant in this, the new age of sustainability. The opportunity existed for development goals, sustainable design, and historic preservation to come together here: Glenridge Hall now serves to symbolize all that is wrong with unregulated, or improperly regulated, development.

References

Craig, Robert M. “Glenridge Hall.” Southern Homes, November-December, 1988.

Stanfield, Elizabeth, William Mitchell, Robert M. Craig, and Elizabeth Dowling. From Plantation to Peachtree Street: A Century and a Half of Classic Atlanta Homes. Atlanta, GA: Haas Publishing Company, 1987.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.