Sitting at the intersection of three valleys in the central Idaho mountains just south of Sun Valley is one of the most enigmatic houses in the West. At first glance it appears to be a wildly chaotic grouping of randomly rounded forms and volumes. Sited in a broad flat area just beyond an intermittent stream and backed up by abrupt foothills, one cannot escape the feeling that it is a puzzle to be solved.

Henry Whiting wanted to build a contemporary example of organic architecture near the resort community of Sun Valley. Though he would live in it initially, it was intended for sale. Whiting had a lifelong love of the landscape around Sun Valley, particularly its gently rolling, dendritically formed foothills, cloaked in a fawn-like skin of sagebrush and grass. These hills are an intermediate ecosystem between the basaltic high desert of southern Idaho and the towering peaks of the Pioneer, Boulder, White Cloud, and Sawtooth mountains of central Idaho. Whiting would watch, mesmerized, as the sun gradually moved across the landscape, creating ever changing shadow patterns on the hillsides. He found the gradual transition from full sun to full shade over the curved masses of the foothills to be particularly lovely. His goal was to build a house that would emulate this character and serve as an example of building harmoniously with the land.

Whiting approached Albuquerque architect Bart Prince with his vision. They had met several years earlier and bonded over Frank Lloyd Wright, organic architecture, and, in particular, their respective mentors: for Prince, Kansas-born Bruce Goff, and for Whiting, his great uncle, architect Alden Dow, who had been a charter member of Wright’s Taliesin Fellowship in 1933. They agreed to work together: Whiting would build what Prince designed.

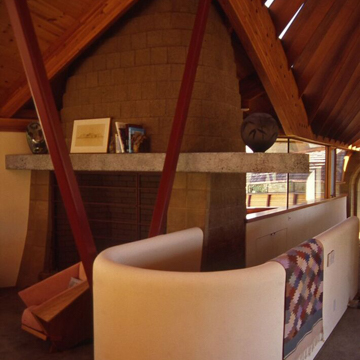

Inspired by Wright’s Prairie Houses, Prince integrated his design into the surrounding landscape. The building is rounded in plan, section, and elevation so that it truly abstracts the masses of the foothills bordering Greenhorn Gulch. It is constructed of split-faced, brown cinder block and wood, stucco, steel, and glass. The color and texture of the block blends beautifully with the landscape. The shell-shaped roofs are supported by massive, curved, glu-lam beams, placed vertically and horizontally, and steel posts, originally painted a brick red color in homage to Wright. The entire structure is raised a half story above the landscape so that the inhabitants can look out over the vast, flat valley floor, an attribute especially appreciated in winter, when the snow can be four to six feet deep.

Standing in splendid isolation when it was first built in 1989, the house was intentionally sited well back from the street on its twelve-acre lot, so that its enigmatic scale would be difficult to discern, adding to the allure of the building. The double roofs, called “cold roofs” due to their bulky air vents at the top and bottom, prevent irregular melting and the formation of icicles by creating an exposed surface with a uniform temperature, although they are cumbersome in appearance. Contractor Jack McNamara and his crew, working with Prince, came up with a brilliant solution for concealing the vents within the curves of the structure so that they are almost invisible.

The long, linear house is oriented at a 45-degree angle from north so that as the sun progresses through the day, the shadows inside and out change and evolve with surprising complexity, traversing across the block walls the same gentle way they move across the hillsides. The house is approached by a long, snaking driveway, which mimics its form and plan and gives one a uniquely three-dimensional introduction to the structure. The house is first encountered at the master bedroom end, where it looks narrow, almost insignificant. Continuing along the driveway, one turns and crosses a bridge over Greenhorn Creek, and the full length of the house is suddenly and dramatically in view. From here the logic of the layout is apparent: three undulating pods are visible, the largest at the center contains the main living areas, while two subsidiary pods, containing the master suite and guest bedrooms, respectively, flank it. Hallways, nicknamed “the tubes” by the workers, connect the pods. They are supported by semicircular bent steel beams attached to the masonry, and are circular in plan and section. These sloping circulation areas lead down to the pods and are among the most unique spaces in the entire structure. The garage doors are hidden underneath the main living space.

The pattern of the entry spatial sequence is another homage to Wright. A curving, inclined ramp leads to the front door. Upon entry through a pivoting door is a low-ceilinged circular entry hall. Passing through an archway in the block wall, visitors encounter the breathtaking main living space, lit beneath the 75-foot-long undulating skylight that connects the two roofs of the main space; it is held aloft by two giant, curving glu-lam beams and four V-shaped steel posts. Proceeding up a ramp, past a seating area into the space, one sees the fireplace ahead on the left, and the kitchen and dining areas to the right. Two hexagonal decks intrude underneath the broad overhanging roofs like sparkling crystals and further differentiate the space. The feeling of an embracing, nurturing space created by the roofs is now palpable, and the logic of the shell-like exterior becomes obvious.

It was Prince’s intention that one would have to walk to all corners of the house and look out each window in order to fully apprehend the grandeur of the surrounding landscape. The whole is never revealed from any one point. It is by fully circulating throughout the interior in search of views of the landscape that one interacts with and comes to understand the architecture. It is indeed a puzzle to be solved, but as with any Bart Prince house it can be—nothing is left to chance and nothing is arbitrary. Every element down to the smallest detail, every curve of the masonry, every angle of the wood structure, now seems effortlessly held together, part of a cohesive whole, which can ultimately be traced back to his seed germ ideas for its purpose and logic. In this it is a great work of organic architecture.

The house remains a private residence.

References

Mead, Christopher Curtis. The Architecture of Bart Prince. New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 1999.