Habitat Disturbed/Watersheds Redeemed

Shaping of buildings and landscapes of north central North Dakota began with the early explorations of the sieur de La Vérendrye (also known as Pierre Gaultier de Varennes) for the Montreal-based North West Company in 1738 and David Thompson in the 1790s, working for the Hudson’s Bay Company’s fur trade. This was well before the arrival in 1804 of Lewis and Clark. The north central region was situated between lands occupied by the Assiniboine to the north and east, and the Mandan and Hidatsa to the south and west. Within the region, the community of Rugby prides itself on being the geographical center of North America. Many historical and geographical factors converge here. Rivers, notably the Souris (also known as the Mouse), flow south from Canada’s prairie provinces and return north into Canada. The James and Sheyenne rivers originate within five miles of each other on a continental divide, with the Sheyenne draining north to Hudson’s Bay and the James flowing south to ultimately join the Mississippi River and the Gulf of Mexico. Plans for a diversion channel from Lake Sakakawea, only partially fulfilled, would have brought the Missouri River across this divide by means of the McClusky and New Rockford canal channels. Adding to the difficulty of agricultural production within the region is that much of the glacial pothole area does not drain to a natural outlet, causing wide fluctuations in ground water tables. All these water issues contributed to environmental calamity in the drought years of the 1930s. Those, in turn, led to some remarkable watershed conservation undertakings and the development of important wildlife refuges.

British and Scottish agricultural investors played a significant role from 1877 to 1910 in agricultural development of this region. In addition to the Great Northern (GN) Railway’s branch line—the Surrey Cutoff—that connected the communities of New Rockford, Wellsburg, and Selz situated between Fargo and Minot, the Minneapolis, St. Paul and Sault Ste. Marie Railroad (Soo Line) served Carrington, Fessenden, Manfred, Harvey, and Velva on a northwest diagonal line from Valley City to Minot. Though few if any architectural remnants associated with early exploration survive, the buildings and landscapes of the region bear hallmarks of Chippewa, French, Métis, and Scottish culture in communities like Bottineau and Sykeston.

Historically the southern half of this region was regarded as agriculturally productive, while land north of Rugby to the Canadian border was more heavily wooded, with much of it lying within the Turtle Mountain Reservation. Forty-five thousand acres of potential farmland in Wells, Foster, and Stutsman counties were purchased speculatively in 1881 from a Northern Pacific Railway land grant and broken for agriculture by well-heeled British immigrant Richard Sykes, who brought in mechanized equipment, teams of oxen, and work crews to break the sod. Several other investment bankers in this region were also of British or Scottish origins. Over time, with the development of farming by immigrant farm families, agricultural fairs and a popular horse-racing culture gave an air of British influence to the central region of North Dakota.

Along with widespread financial collapse, the glacial outwash Prairie Pothole Region of prairie wetlands and the fluctuating James, Sheyenne, and Lower Souris drainage basins were devastated by drought from 1931 to 1937. Great Depression-era work relief projects and the restoration of wildlife habitat were undertaken mainly by crews of the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC). Much of the emphasis shifted from productive agriculture toward resource conservation. Under leadership of a federal-sponsored biologist and wildlife specialist, Clark Salyer, CCC crews based in camps near Kramer, Bottineau, Kelvin, and Dunseith rehabilitated some of North America’s first wildlife refuges and restored critical habitat areas. They stabilized the environmental disaster while charting a more realistic course for managing rural lands for the longer term. The town of Towner and an area south of Denbigh became important sites for nursery development of planting stock used for shelterbelt (windbreak) construction in all parts of North Dakota, and the state’s School of Forestry is, today, based in Bottineau. A side effect of this retrenchment, perhaps inevitable, has been that many small communities have withered and disappeared along with many noteworthy buildings. Most of the towns exuded a strong connection with the railroads, lumberyards, grain elevators, and railroad hotels.

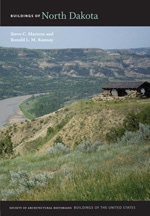

Several communities in this region, Bottineau in particular, have a rich building tradition of stonework, drawing on the experience of Scottish stonemasons and the availability of glaciated fieldstones, sometimes referred to as “glacial erratics.” The tradition of landscape design in this region is evident in the many rehabilitated wildlife management areas. The visionary International Peace Garden (RO4) bridges the North Dakota-Manitoba border as a lasting tribute to world peace and is a site for music festivals and floriculture. State government investment in a remote tuberculosis sanatorium at San Haven also precipitated some extensive landscape development of its campus. But with different medical options, the San Haven campus has been abandoned and has undergone a long, painful process of piecemeal demolition.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.