Cultures Displaced/Culture Superimposed

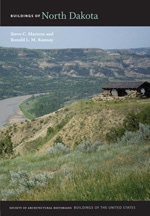

Though the Badlands are present in only part of the southwestern region, the region’s landscape was shaped by erosion from the Little Missouri River on its northerly course to the Missouri River. The Little Missouri’s high banks are layered with scoria, clinker, and coal. The underlying sandstone and limestone, together with this region’s origins as part of an ancient inland sea, have yielded several unusual features. An impressive range of dinosaur fossils have been discovered in the area from Dickinson to Marmarth. Buttes were traditionally a method of orientation and wayfinding, and more recently several have been overtaken by clusters of telecommunication towers. In the early days of European settlement, petrified wood was rather carelessly harvested in several locations within Theodore Roosevelt National Park and incorporated into buildings. Burning coal seams occur at several remote locations.

An earlier tradition is embodied in the quarrying of Knife River flint stone by Native American people in protected locations in Oliver County. The Cannonball and Heart rivers flow eastward toward the Missouri, and the Heart River, in particular, was the cultural hearth of the Mandan and later Hidatsa before their relocation northward to village settlements near the Knife River under pressures from the Hunkpapa and Teton Dakota-Sioux. The Knife River Indian Villages (ME2.1) site, a National Historic Landmark, is especially well interpreted for its cultural and architectural significance. Traditional lands of the Teton Dakota-Sioux were centered along the Missouri River-South Dakota border south of Bismarck-Mandan, particularly in modern-day Sioux County, where ancient stone effigies and astronomical markers are said to exist on protected sacred sites. The burial site of the Hunkpapa Lakota holy man Sitting Bull (see SI1) is commemorated near Fort Yates, although his body is generally assumed to have been later exhumed and reburied elsewhere.

From 1862 to 1877, a series of running battles, known collectively as the U.S.-Dakota Wars, occurred between Dakota warriors and U.S. military troops near the North and South Dakota borders with Montana. They were generally associated with penetration between 1871 and 1873 of the Northern Pacific (NP) Railway and with federal government policy geared toward forced displacement of Native Americans from their ancestral homelands. In 1874, Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer forged an expeditionary trail from Fort Abraham Lincoln (MO5) through southwestern North Dakota to the Black Hills of South Dakota. Surviving features of that man-made military landscape remain visible at Fort Abraham Lincoln. Much of the interpretation of the site is also associated with the presence of Custer’s cavalry troops.

The NP opened the region to ranching and encouraged tourism by promoting such geological features as Pyramid Park and the Badlands. In the 1920s and 1930s era of automobile tourism, a series of gravel and paved roadways were linked and advertised as the “Red Trail” (U.S. 10, now I-94). Few vestiges of that era remain today along I-94. As with the northwest region, the southwest counties are currently experiencing substantial pressure from oil field development, impacting the quality of life and architectural heritage of many communities.

Between the completion of the NP at the Little Missouri crossing (present-day Medora) and the automobile tourism era that gave rise to “dude ranches” in the Badlands, a series of peculiar local events gave the fledgling community of Medora much wider visibility and historical importance. A French nobleman, Antoine de Vallombrosa, the Marquis de Morès, with investment ties to the eastern United States, devised a plan to ranch cattle on open range grassland on the northern Great Plains, and slaughter them in Medora for commercial shipment to eastern markets in refrigerated railroad cars. A number of features remain from this enterprise, including a memorial park (BI5), ruins of the packing plant (BI7), and the Chateau de Mores (BI8). At the same time as the marquis’s investments, Theodore Roosevelt became a rancher and resident of the area, which he credited as formative in his progressive visions of landscape conservation. Many of the historic events and buildings associated with the marquis and the Roosevelt era in Medora are reinterpreted for tourists today with varying degrees of veracity. Ranching culture and Native American associations with the Little Missouri country are interpreted in the North Dakota Cowboy Hall of Fame Museum ( BI6) in Medora. In 1978 Theodore Roosevelt National Park was finally designated as North Dakota’s only national park, with a South Unit (BI9) and a separate North Unit (MZ3) in McKenzie County. From 1934 to 1942, CCC camps were located in both North and South units, completing important and environmentally sensitive development work under management of the National Park Service and the State Historical Society. Architectural amenities from that era remain some of the park’s most important historic features.

Like the de Morès ranching enterprise, expansive visions have always been part of the broad landscapes of the southwest region. Their legacy remains visible in many forms. The small town of Marmarth, with its outsized architectural pretense, emerges from the southern Badlands at the Little Missouri crossing of the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul and Pacific Railroad (MILW). Contemporary and different visions are embodied by the overscaled sculptures of the Enchanted Highway (SK2) and St. Mary’s Catholic Church and Assumption Abbey (SK1) in Richardton. The abbey was conceived as a place for the educational training of the hundreds of new priests that would be needed to serve German-speaking immigrants.

Many of the agricultural communities the immigrants built retain a unity of cultural vision evident in the buildings and commemorative landscapes, including the cemeteries with their hand-wrought iron crosses. Although much of this material culture is rapidly disappearing due to neglect and environmental abuse, Belfield is the site of a remarkably well preserved domed Ukrainian Orthodox church (SK11) and a number of historically important buildings are in Dickinson. To the east of Richardton, two notable forms of regional economic development are represented in the brickmaking industry of Hebron (MO11) and the dairying industry surrounding New Salem. The importance of localized community and small county seats is reflected in several courthouses. The large service center city of Mandan is across from Bismarck on the west bank of the Missouri River.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.