A Landscape Transformed by Extraction

The northwestern region of North Dakota is historically important for Lewis and Clark’s expeditionary encounters (1804–1806) with Mandan and Hidatsa people. Near today’s community of Washburn, they were introduced to Native American guide Sakakawea, who enabled their successful travels up the Missouri River and across the Rocky Mountains. Historic trade ties are commemorated at the reconstructed Fort Union Trading Post (WI7) on the Yellowstone River west of Williston, but there was vigorous trade among Native Americans throughout this region before Euro-American contacts. Other constructed features like Fort Buford (WI8) in the northwest and the engineered modifications of the Missouri River reservation lands of the Three Affiliated Tribes point to a much darker and tragic side of European exploitation of the northwest region.

The buildings and landscapes of northwestern North Dakota were shaped in the 1880s by the Great Northern (GN) Railway and the Minneapolis, St. Paul and Sault Ste. Marie Railroad (Soo Line). The Soo built a line from Valley City that reached Minot in 1893 and later continued the line to Canada. The transcontinental GN competed for passengers and freight traffic with the Northern Pacific (NP) Railway, which followed a more southerly route across North Dakota. The railroads brought waves of immigrant settlers, predominantly Scandinavians. An annual celebration, Norsk Høstfest, and a park commemorate those cultural ties. Enclaves of Germans from Russia comprise another substantial cultural core in the region.

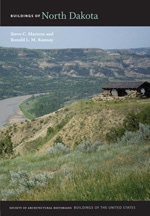

Water and coal were important mineral resources, first identified by early explorers and exploited through most of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Localized coal extraction was important northwest of Minot, extending from the Burlington area to Crosby in the state’s far northwestern corner. Coal was also mined near Wilton and on the south shores of the Missouri near Beulah and Hazen. In the 1970s, a much more expansive approach to coal surface mining was undertaken in the vicinity of Falkirk, in southeastern McLean County. Coal was extracted at an enormous scale for electrical power generation at the nearby Coal Creek Generating Station, Antelope Station, and other electrical power plants that feed into the national transmission grid alongside the Garrison Dam hydroelectric station (see ML4). The discovery of oil near Williston in 1951 produced a boom of scattered oil well production in the 1970s, superseded in the first decade of the twenty-first century by the astonishingly transformative extent of shale oil production from the Bakken geological formation, where the new technologies of horizontal drilling and fracking are employed. Farming and cattle ranching remain important, as does the investment of the federal government in projects like the Minot Air Force Base and the Garrison Dam.

Most buildings associated with the Mandan-Hidatsa-Arikara cultures have been erased from the landscape, including a once-important dance lodge from the post-contact period in Elbowoods. Many small rural communities maintained their immigrant ethnic and cultural associations through several generations, an architectural legacy that is subtly visible in churches, barns, and the distinctive construction methods used in rural schools and houses. A few imported building traditions are more recognizable. The Danish Windmill (WD17) in Kenmare and the onion-domed Holy Trinity Ukrainian Greek Orthodox Church (ML1) in Wilton can fairly be considered two of the region’s most important examples.

The architecture in most communities, though, reflects considerable assimilation and adoption of Americanized practices of commerce and service. Since many of the earliest commercial buildings survive unaltered in towns like Epping, boomtown commercial fronts are a prominent feature by which modest architectural style was applied to straightforward gabled, wood-framed structures. Opera houses as in Ray and Kenmare and motion picture theaters as in Kenmare and Crosby were recreational outlets and allowed occasional flights of fantasy, though most in the northwest region are modest in their use of Art Moderne motifs.

For schools, courthouses, and other public buildings, architects from Minot and Grand Forks had convenient railroad access to clients in communities served by the GN. Commercial buildings, especially in Minot and Williston, reflect a more adventurous quality in their up-to-date approach to design. Railroad hotels in such towns as Kenmare and tiny Noonan reflect the importance of commercial travel, and rail service, though diminished, continues to the present day.

In the 1920s, the northwest region manifested political discontent and grassroots reform activity under the populist Nonpartisan League. With the onset of the Great Depression, buildings from federal work relief programs are especially visible in western parts of North Dakota. Because of the fairly late formation of many counties, a number of county courthouses were also constructed during the Depression. Less visibly, west of Minot and adjoining the community of Burlington, the federal Resettlement Administration funded a remarkable “stranded community” for resettlement of coal miners from the faltering Oliver mines, including a series of flood control and irrigation dams on the Des Lacs River, and thirty-five units of small farmsteads, all of which was later renamed the Judge A. M. Christianson Project. This historic enclave survived intact until compromised by flooding in 1969. In 2011, the Christianson Project, like Minot’s Eastwood Park neighborhood and Roosevelt Park Zoo, was again inundated by major river flooding. Here, a small percentage of historic buildings have been rehabilitated, but the historic water control infrastructure, dams, diversion canals, roadways, and some houses have been erased. In the course of constructing the earthen dam south of Garrison in the 1950s, a new town was developed for construction workers and named Riverdale. Other planned new resettlement communities on reservation lands (New Town, White Shield) were built by federal agencies for resettlement of Native American communities from permanently flooded communities near the Missouri River. Few of these planned communities have evolved a strong, sustainable sense of identity.

After a major commitment to improved flood control and rehabilitation, many communities on the Souris, Des Lacs, and Missouri rivers again experienced record-setting floods in 2011. Recovery from those floods and peripheral impacts from unfettered oil field development in the northwest region upon the long-standing architectural heritage of communities remain a story in progress.

During the 1960s and 1970s, national energy experts and development-minded politicians suggested that all of North Dakota might simply be written off as an energy sacrifice zone, consuming and exporting a variety of forms of energy to the East and West coasts. In a manifesto of 1973 that came to be known as When the Landscape Is Quiet Again,Governor Art Link advocated a longer view of cautious, orderly development and restoration of disturbed landscapes as part of the inherent cost of resource extraction.

In the first decades of the twenty-first century, there have been several local endeavors to preserve features of the region’s architectural heritage. However, the pressures of development are extreme, and when buildings are lost, the cultural traditions they embody are lost forever. These lessons continue to be relearned in the present day.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.