Dryland Agriculture in the Sauerkraut Triangle

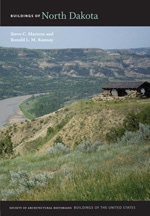

The buildings and landscapes of south central North Dakota were shaped by Germans from Russia, who patiently imposed their substantial agricultural capabilities on the dry lands of the northern Great Plains. Most of the towns in the south central region retain a strong association with their German-speaking heritage, notable for language, foodways, music, ethnically distinct churches, and cemetery traditions. There are a number of excellent examples of traditional German Russian folk housing, like the Johannes Goldade House (EM3) east of Linton, that are well preserved because of their continued use until after World War II. German Russian agriculturalists resisted cultural assimilation, disdained academic education beyond the basics of elementary school, and prided themselves on economic conservatism that contributed to grim, hardscrabble survival through the drought years of the Great Depression. Early settlers walked miles to gather buffalo bones to sell by the railcar load at railroad towns for transportation east to make fertilizer. Buildings were generally constructed with modest aspiration for stylistic embellishment, but with a strong sense of making things last.

This is the geocenter of German Russian architecture—churches, mass wall houses, and connective housebarns. The Ludwig and Christina Welk Homestead (EM5) near Strasburg displays unfired batsa brick construction and other typical aspects of German American farm life on the Dakota prairies. Renewed local pride in architecture and cultural heritage is celebrated through the Germans from Russia Heritage Society, the North Dakota Heritage Center, and by strategic investment in cultural heritage and heritage tourism.

Economically important buildings throughout this region include the clusters of grain elevators where wheat and other small grains were consolidated in vertical cribs and were gravity fed to railcars. In most growing seasons, North Dakota is the nation’s largest producer of grains like spring wheat, barley, oats, rye, millet, flaxseed, and canola. The establishment and growth of counties and communities were entwined with the routing and construction progress of the railroad, with fledgling townsites occasionally abandoned or relocated. Most towns in the south central region were connected by the Northern Pacific (NP) Railway main line, but other towns, such as Linton, were served by short branch lines or connecting spurs. Linton was once the site of quarrying dark gray sandstone, one of North Dakota’s few indigenous building materials.

Within the prevailing context of farmland and small agricultural service towns, the state capital, Bismarck, impresses as an anomaly. It also confirms the commitment of pragmatic rural settlers to efficient, populist governance. Bismarck emerged as the territorial capital prior to statehood. The first state capitol building, an Italianate structure of 1884, was destroyed by fire in December 1930. Fragments of the first capitol’s sandstone trim are found scattered around the parking areas near picnic shelters at Fort Abraham Lincoln (MO5), south of Mandan. The building (BL1.1) that replaced that capitol is a restrained and economically detailed Art Deco design that set the standard for public buildings in North Dakota from 1934 onward.

As the center of state government, Bismarck grew to have substantial civic and institutional buildings, as well as prestigious residential neighborhoods associated with governmental officials, lobbyists, and lawyers. The State Historical Society, too, has been an important component of the capitol master plan since the historical agency was effectively organized in 1904 by Dr. Orin G. Libby. There was visionary growth in the Historical Society’s missions during the 1930s under the leadership of Russell Reid, which saw the development and dedication of numerous state historic sites.

Among architects working prominently in the south central region were Ritterbush Brothers, Arthur W. Van Horn, and Gilbert R. Horton, who had a long and distinguished career in Jamestown and completed a substantial number of important buildings during the Great Depression. Horton was also a vigorous advocate for early automobile tourism and better roads. The south central region is a powerful, appealing landscape, with strong ethnic influence on the architecture of its small towns.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.