Gateway to the Northern Plains

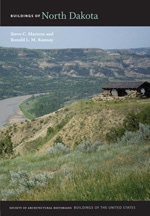

The southeastern region of North Dakota is characterized by its early agricultural success through a series of speculative bonanza farmland developments and by the establishment of two transcontinental railroads. In 1858 Fort Abercrombie (RI6) was established on the Red River of the North on water navigable for steamboat traffic heading north to the Selkirk colony at modern-day Winnipeg in Canada. But the steamboat era on the river was brief. Attracted mostly by a fifty-million-acre land grant chartered in 1864, the Northern Pacific (NP) Railway crossed the Red River at Fargo in 1872 and reached Bismarck just twelve months later. The railroads influenced town siting and development of the rural countryside. Fargo and Valley City are the region’s principal cities.

The real gold in the Red River Valley of the North proved to be agriculture, and specifically, a particular kind of hard red wheat. The First Great Dakota Boom began in 1878. Investment capitalists speculatively bought and consolidated land from the NP, and established a new approach to growing wheat on “bonanza farms” that were as large as thirty thousand acres. In Nature’s Metropolis: Chicago and the Great Midwest (1991), William Cronon describes the two-way pipeline the railroad provided, with agricultural machinery and equipment flowing in from markets in eastern Wisconsin and the southern Great Lakes region, and an insatiable market for wheat in the milling district of Minneapolis.

Because settlement was directly tied to the progress of the railroads, speculative townsites were platted by railroad companies along the NP and, later, the Great Northern (GN) Railway and other railroad routes. Communities succeeded or failed based on their accuracy in predicting where the railroad line would locate. In many respects, the planning and speculative land development for so many small towns was impractical to sustain. Elwyn Robinson’s classic History of North Dakota (1966) addresses the “too much mistake” that necessitated retrenchment. Economic panics that jeopardized the railroads also constrained investment in the communities they supported. Many cities and towns on the Great Plains were, at some point in their history, destroyed by fire.

Each railroad company had its preferred model layout, or plat, often emanating from a Front Street alongside the rail line where lumberyards, grain elevators, railroad hotels, and other early infrastructure were placed. Lumber yards were the source of most of the materials used to build farmhouses and barns, rural schools and country churches, and enabled Main Street businesses and governmental centers, all the necessities of westward-spreading American culture. Grain elevators became the distinctive feature of the Great Plains landscape. Though nearly all North Dakota communities were served by railroads in 1900, a century later the tracks have been abandoned and dismantled in many small towns, leaving stranded elevators without an outlet for even local grain production.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.